Recent revelations on how foreign governments are using NSO spyware to hunt journalists and political opponents is another example of a prevalent norm in our online society: digital surveillance. Data exploitation by the powerful is also reflected in the way online advertising infrastructures (AdTech) are profiling individuals for targeted advertising, or by the ability of law enforcement officers to enhance facial recognition through the Clearview AI product, linking facial images to online presence by analyzing our publicly available images. Our heavily surveilled digital society creates ample opportunities for data exploitation, and without clear digital accountability mechanisms, divergence is unlikely.

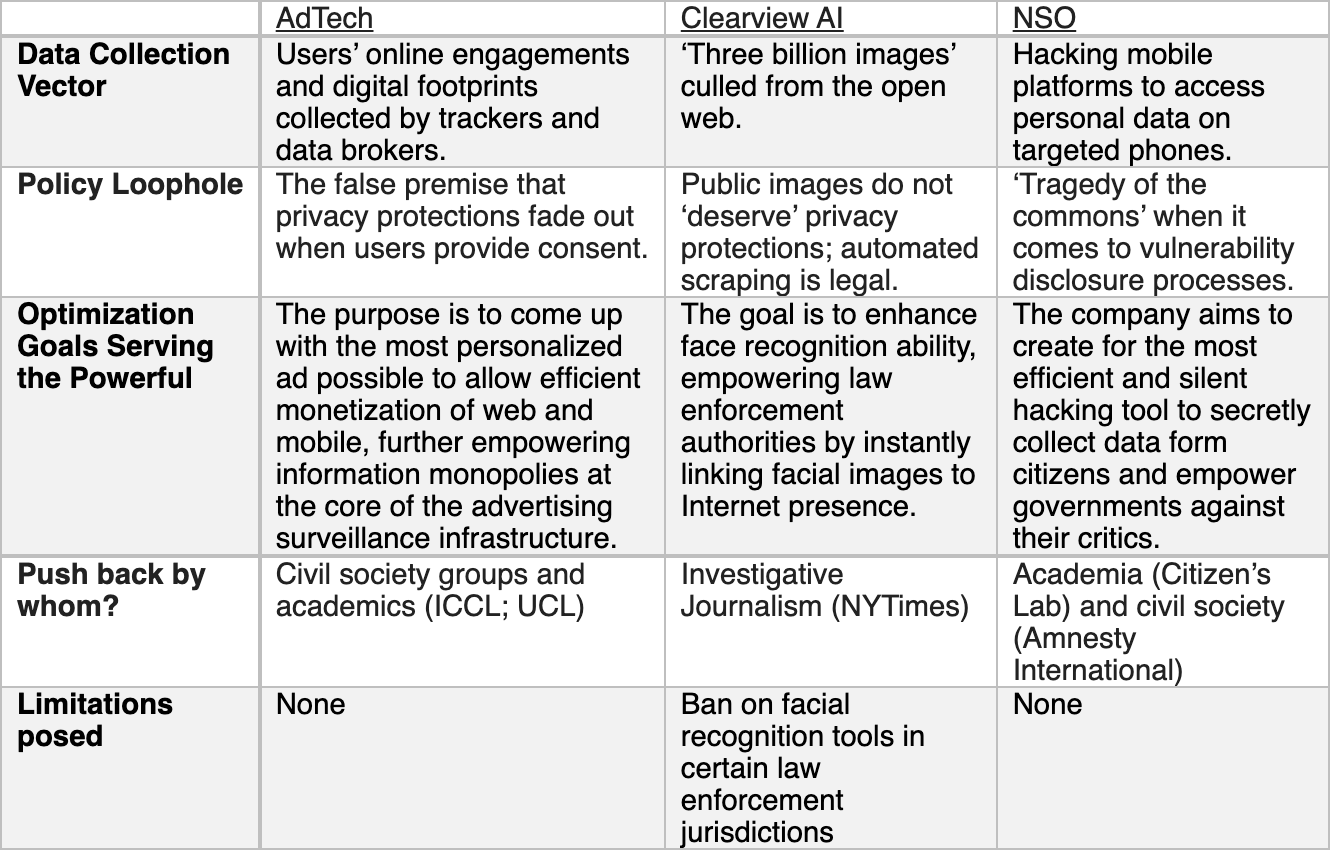

The different data exploitation paths differ on the technicalities, but all operate under the same principles: (i) Policy loopholes are utilized to massively collect and analyze our digital traces; (ii) Data optimization goals serve a few at the expense of the fundamental rights of all the others; and (iii) Counter responses emerge only thanks to bottom-up actors from academia and civil society who monitor and shed light on these disturbing practices. But despite revelations and clear indications on how bad this is for our society, no significant change is on the horizon.

Comparatively assessing three cases of digital surveillance clarifies the chronic of those failures, highlighting what is at play when yet another persistent path of digital surveillance is established.

AdTech Infrastructures

Online advertising infrastructures (AdTech) normalize the presence of third-party software in our websites and mobile apps for tracking and monetizing purposes. Online tracking is embedded in almost every facet of our Internet ecosystem, enabling real-time-bidding on ad spaces based on dossiers collected on individuals by data brokers and trackers over time. Google and Facebook are dominating those tracking efforts with the whole industry coming together through its association, The Internet Advertising Bureau (IAB), that oversees a ‘consent framework’ that allows opaque industry actors to get users’ personal data without users fully understanding the implications of their consent decisions.

Tying together privacy regulations with consent is strategically used by the powerful to track and ‘fingerprint’ users, construct profiles against users’ expectations by linking fragmented parts of their identity, and create a culture of ‘surveillance-by-default’ for anyone who is engaging online. The goal is to provide the most targeted possible ad in real time in order to maximize profit at the expense of individuals’ privacy. It is only thanks to massive efforts by civil society groups and academics who revealed and filled complaints about this troubling trend, with regulators still hesitant to take decisive actions and change the course of our online experience away from consistent surveillance.

Clearview AI

The Clearview AI case has been following the same trajectory. The for-profit company has been scarping and analyzing publicly available images from the Internet, gaining legitimacy from law enforcement officers who are buying and using these tools to enhance their facial recognition efforts. The company has been utilizing yet another privacy policy loophole according to which public images (“three billion images” in this case) are not entitled to privacy protections and can therefore be used by anyone, with almost no limits. The company made it easy to instantly connect a person with its online footprint, collecting images from public websites like Facebook, YouTube, and Venmo.

Even though such automated scarping violates Twitter and Facebook privacy policies, it did not stop the company from accessing and using those public images, under the assumption that since they are public, “everything goes.” The court ruled that ‘scraping’ a public website data is not hacking, contributing to conflicting views on the social value of automated scraping, further blurring the boundaries on how publicly available information can be exploited.

Data optimizing goals in this case are meant to work against the ‘bad guys,’ by being used to better recognize criminals. In reality, however, facial recognition tools lead to wrong arrests, racial discrimination, and overall decreased police accountability. With an ever-heavy reliance on machine outputs, humane police decision-making might fade out. Push-back on these efforts was only possible following investigative journalism efforts by Kashmir Hill from The New York Times, who was persistent enough to bring Clearview AI out of the shadows. Her stories created a domino effect with a few local authorities banning face recognition altogether. How far-reaching this opaque tool actually is and who is held accountable for its mistakes remains unclear.

The NSO Group’s Pegasus Spyware

A similar pattern is evident in the case of NSO Group’s Pegasus Spyware. A for-profit hacking industry empowers governments to efficiently hunt regime critics and opponents by secretly collecting intimate information from their phones, utilizing policy gaps in vulnerability disclosure processes. According to a study by Forbidden Stories in partnership with Amnesty International, the program was used to tap into at least 37 smartphones belonging to journalists, human rights activists, business executives, and others.

The revelations of the widely accepted norms of government surveillance demonstrate how governments have little interests in agreeing on an international treaty to limit cyber surveillance. Leadership on policy initiatives that would require full disclosure of vulnerabilities found in operating systems or services of computing devices is absent as well. Discovering digital vulnerabilities is the core operation for intelligence agencies around the world, and for-profit industries are utilizing the legitimacy of government surveillance to equip less-capable governments with advanced hacking tools, allowing state leaders to deploy surveillance operations against any device they desire.

This is a classic example of the ‘tragedy of the commons’ – everyone is acting independently according to its own self-interest, without considering wider, long-term implications to cyberspace security. As such, they further deteriorate the security and privacy of us all. With states themselves as the customers of the surveillance industry, it is unsurprising that the spyware industry continues to be largely unregulated.

These digital surveillance tools found their way to dictators hunting journalists and civil activists to maintain in power. It was only thanks to efforts by academia and civil society that revealed those industries, creating an important debate about these troubling practices under the public eye.

This quick comparative assessment clearly shows how market and state powers are normalizing surveillance and data exploitation.

We are stuck in this feedback loop for quite a while now, with regulators mostly unsuccessful in limiting the different surveillance efforts. For instance, UK’s data protection authority, the Information Commissioner Office (ICO), declared in June 2019 that AdTech infrastructures clearly violate the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), but has done nothing since. Clearview AI products have been used by many and limited only in a few cases. For-profit hacking is a thriving industry, with other examples include the Hacking Team, Paragon, and Candiru, with no limits on the horizon. There are a few exceptions, but a significant effort to change the way we govern our digital society still awaits.

What Can Be Done?

Our digital society is evolving with very little accountability. Software companies are not liable for their flaws, governments are not liable for their hacking, information monopolies are not liable for the content they manage and its implications on society, and the list goes on. Our path away from digital surveillance is through injecting digital accountability into our institutions, industries, and governments.

Accountability has been widely debated in the public administration literature. One of the fundamental conceptualizations of the term comes from Bovens (2007), who views accountability as a three-phase actor-forum relationship that includes:

-

Information provision by the actor to the forum (e.g. security agencies provide information to elected officials on how they use spyware software).

-

Explanation / justification of actor’s decisions to the forum (e.g. security agencies explain to elected officials which vulnerabilities they chose to utilize and why they chose to hunt specific individuals).

-

Potential consequences for the actor that are shaped by the forum (e.g. politicians can sanction security agencies for abusing their powers).

Each of these interactions can pose limitations and oversight measures on the prevalent surveillance practices discussed above, so industries and government agencies need to respond to political, social, and professional accountability forums.

Thus, to strengthen digital accountability and lead us away from surveillance, we need to strengthen each of those ‘accountability forums:’ To improve the way politicians are holding surveillance industries into account we need a better privacy enforcement process. This means strengthening already existing privacy agencies – The FTC and the EU data protection authorities. Historically, their enforcement approach has been heavily criticized for being soft on industries, and their resource and expertise constraints are perceived as preventing significant administrative actions against privacy violations. To improve top-down enforcement, new US data protection agency was proposed, FTC leadership change is starting to signal a new enforcement tone, and more administrative transparency and resources were advocated for in the EU.

These are all welcomed changes, that can help in the AdTech case, but to create meaningful state surveillance accountability, we will need completely new processes that strengthen police accountability and set new digital vulnerability disclosure standards. These are far-fetched changes, that are unfortunately disconnected from efforts to strengthen users’ privacy from non-state threats. These processes only start to emerge, currently preventing meaningful political accountability over government surveillance.

To strengthen social accountability and improve the way media and civil society can hold surveillance industries into account, we have seen several ideas to empower users by allowing them to own the rights over their data. This would inject transparency into data exploitation efforts, enabling a more meaningful debate on currently opaque data brokers industry that feeds commercial surveillance efforts. Representation of data subjects, one of the novel clauses of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), is another step in the right direction. The clause allows NGOs and activists to develop expertise and hold giant firms into account, in ways that private individuals are unable to pursue without such intermediation. Expertise gaps have been narrowed by academics as well, but this has been quite an exception. We are still heavily dependent upon investigative reports and whistleblowers for questioning government surveillance practices, with responsible governance in this space seems far-fetched.

The idea of professional accountability, through which actors are held into account by their peers and expert groups, has been promoted as well. Jack Balkin (2016) came with the idea of assigning special status to those who handle our personal data, classifying them as ‘information fiduciaries,’ which would require certain degrees of trust and honor to the way they handle data. This is a special category for those who hold troves of information about individuals, creating duties that do not harm the interests of data subjects.

Just like doctors and financial advisers, those who hold personal information should be trusted by data subjects and are obligated to respect users’ information and treat them fairly. This should be prior to any attempt to ‘become creative’ by using personal data in new ways. This new status might create a ‘code of honor,’ or an incentive for other ‘information fiduciaries’ to signal those who violate the norms. Users struggle to hold data owners into account, so a new sort of fiduciary obligation might create new standards in this space.

While this idea is still far from reality, creating a new status – and therefore new professional and ethical standards for information owners – might pave the way for new interactions of professional accountability which are seriously lacking in this space. This should include not only for-profit actors but also governments that should be trusted or held internationally accountable by other states, with possibly facing sanctions in case they violate trust codes of data collection and analysis.

With digital surveillance and data exploitation being so rewarding for the powerful, injecting digital accountability by strengthening political, social, and professional accountability forums might gradually take us away from those disturbing norms, toward hopefully a brighter digital future.