If knowledge is power, power also requires knowledge and the ability to restrict access to some knowledge.

At the most fundamental level, our national security secrecy system is about knowledge. To protect and defend our nation and our allies, national security departments and agencies want to know as much as possible about the views, intentions, activities, and capabilities of other governments and transnational criminal groups. Conversely, there are programs and capabilities of ours which would be less effective were they to become known in detail by competitors and potential adversaries.

These requirements to know about others while limiting what they know about us lead to some information being classified and access restricted to those who need it to do their jobs. If the targets of our information collection learn how we acquire it, they may be able to block our future access. If competitors and adversaries learn the details of programs and capabilities that protect us or give us an advantage, we could become less safe or secure.

Those basic facts have caused most national governments to have secrecy systems and have done so for centuries. Because the United States has global interests and presence, what we may potentially need to know and prevent others from knowing about us is vast, as are our capabilities to collect and process that information. The result is that there are billions of pieces of data in US government secrecy systems.

The very existence of that trove of secrets may seem to some to be a problem until something such as 9-11 occurs, and people ask why we did not know more.

In my experience of handling thousands of pieces of classified data a week for over thirty years, very little secret information I saw was undeserving of that classification at the time it originated. Certainly, there are instances when some in government overclassify information to cover up errors of omission or commission, but I think those instances are a minute percentage of secret data.

No one knows if my assumption about such misuse is accurate because there has never been a census and analysis of US government classified data corpus, nor could there be.

The more prevalent problem is that some data remains restricted long after it needs to be. The chief reason is simply the cost of having a declassification review system large enough to deal with the volume of classified data.

Two systems within the world of classified data help identify and protect some of the information most clearly requiring its control. The first is so-called codeword controlled information, reports the exposure of which would reveal a sensitive intelligence collection source. The second system is that of Special Access Programs (SAP), data about weapons and activities that would be far less effective if adversaries knew them in detail.

Mishandling of classified information from either of these systems could potentially be highly damaging to our national security. Media reports have indicated that documents mishandled by President Trump and or his staff included both codeword and SAP documents. Whether President Biden’s documents included these sensitive types of information have not yet been disclosed.

We should be able to know where any specific piece of classified paper is at any time, but we often do not. National security agencies regularly track documents using control numbers, logs, receipts, cover sheets, and even padlocked briefcases. Papers, however, can easily be photocopied or mislaid. Unlike library books, most classified papers do not have dates by which they must be returned to their originator. When secret documents are reported to have been destroyed in an approved manner, there is no way to confirm their destruction.

Electronic data can be more easily controlled. Software exists to limit who can access specific data, confirm the readers’ identity using biometric controls, and determine who can edit, print, and forward it. All of that activity can be logged, noting who did it and when. Access to electronic data can also be geo-fenced so that it can only be seen in authorized locations.

Because of those advantages, intelligence agencies began using highly secure Read-Only electronic devices to distribute the presidential daily intelligence report several years ago. No reports conveyed on those devices have gone missing or shown up years later in country clubs, hotels, garages, or think tanks.

None of those devices have been lost, but had they been, information on them could have been remotely wiped. If a person were no longer eligible to read classified information, their device could simply be disabled.

There are potential cyber security risks with any electronic device. Still, the US government has for decades demonstrated its ability to successfully secure some sensitive electronics, such as code machines and nuclear weapons controls. It can be done. It’s time we created more secure devices to disseminate as much sensitive information in our government as possible. If we do, we will likely spend less time hunting down mislaid or stolen secrets in the hands of former high-level officials or asking who had access to those secrets.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________

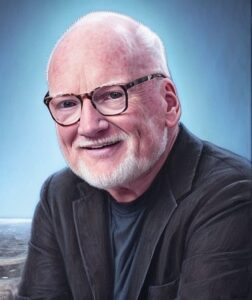

Richard Clarke

Clarke served 30 years in national security positions, including in the Pentagon, the Intelligence Community, the State Department, and the White House (richardaclarke.net).