Although the outcome of the 2020 presidential election may be different from that of 2016, very little is different underneath. The election ended with the presidential race almost evenly split between two different Americas with two very different visions of the country. Thanks to small shifts in the vote distribution in the three “Blue Wall” states around the Great Lakes – due more to turnout than any sea-change in opinion – Democrat Joe Biden was able to flip the election outcome. Republicans have likely kept control of the Senate, gained seats in the House, and increased their margins in state legislatures.

This election follows a Democratic wave in the 2018 midterms. It’s safe to say that the backslide amongst Democratic candidates this time around amounted to less an embrace of Republicans than simply a settling into the current equilibrium. While Republicans are advantaged in state-based institutions like the Senate, Democrats still prevail in the overall popular vote for Congress or the presidency.

Part of the reason for the American electorate’s overall inflexibility is that views across almost all issues have developed a sort of rigid “cross-inelasticity.” In other words, someone who has particular views on environmental sustainability, for example, will most likely hold similar views on other, ostensibly unelated issues like marriage, Israeli-Palestinian relations, and the constitutionality of the individual mandate. Voters today pretty much buy into the full menu of positions of one party, or the entire smorgasbord of views of the other (and Republicans even went so far this year as officially to declare that their platform is whatever Donald Trump says at any given moment).

In ancient days before today’s political alignments, Michael Barone, one of the original editors of the landmark Almanac of American Politics, developed a typology of officeholders and voters based on whether they could be considered liberal or conservative. He based these characterizations on three variables: social issues, economic policy, and foreign affairs. This meant there could be as many as eight political types. Today, Americans rarely care about foreign affairs. Issues such as trade sanctions against China, cyberthreats from Russia, or Central American immigration melt into the domestic culture wars and economic concerns.

This leaves us with just two political types: those who are liberal on everything and those who are just as uniformly conservative.

This runs counter to the realities of almost every other area of daily life today. People mix-and-match their individual preferences for everything else: from niche cable channels and personalized “skins” for their computers, to precisely how they want even their mass-produced burgers prepared. It also diverges from politics itself in most other countries, where if you don’t like a party’s position on a particular issue, you form a new one, so parties proliferate. In the United States, “our electoral system channels voters into putative-majority coalitions (our two parties) before rather than after elections,” but that hardly dictates that voters adopt one or the other platform lock, stock, and barrel. Nevertheless, that’s what we seem to have done.

However, the first glimmers of some break in that gray uniformity may have appeared under the surface of this year’s results. These, in turn, could signal the ultimate direction of a further realignment of American politics. It is one that is away from the realignment we have been undergoing for the past quarter-century culminating in our current divisions. The returns hint at least two significant subgroups worth watching – suburbanites and minorities – for the developing splits within them, which seem to be driven by a split between their economic and social perspectives.

By way of illustration, outside the three Rust Belt states that “flipped” narrowly – a result of turnout, not underlying change – there were two states that presented dramatically different scenarios from Election Night four years earlier: Georgia and Arizona. These shifts have been long predicted, as have similar changes in Florida, Texas, and North Carolina that have not yet materialized. The usual reasons for assuming a “Blue Shift” in these states are the growth of both the metropolitan and Hispanic populations – arguments also extended nationally to the assumption that the country has an ascendant progressive majority due to both the growing urban/rural split and increasing diversity.

Both of those rationales should be given serious reconsideration after this year’s election returns.

Suburban Stasis

Let’s start with suburbia. The setbacks Republicans suffered here were largely Trump-specific – and were nowhere near as significant as heralded by the polls. For instance, as this analysis from the New York Times shows, the suburban movement was reasonably small and concentrated mostly in those that were already closely divided. Those already dug into their views weren’t moving.

Biden supporters have interpreted this as a tacit endorsement of Trump’s race-baiting, misogyny, and xenophobia. This analysis isn’t fair: Trump’s personality repels suburbanites. Most polling suggests that the George Floyd murder and similar events this summer did bring about a positive racial reckoning for much of white America, particularly in the suburbs.

But progressive cultural values are not central to these voters’ identity. Economic security also is. They like Trump’s economic policies, and the economy has been excellent for the last four years except for the coronavirus-induced recession, which they don’t hold Trump responsible for. Perhaps most importantly, Trump cut taxes.

Except for a very brief period at the end, which reversed itself by election day, most Americans continued to say they approved of Trump’s handling of the economy and believed he would do a better job than Biden. Democrats, on the other hand, seem to have an increasingly “socialist” whiff about them. Indeed, Biden’s margin in Arizona ended up narrower than expected largely because of his failure fully to close the deal with Maricopa County suburbanites, particularly in the less-upscale West Valley. (Hispanic voters in the city of Phoenix are what put him over – though, again, by a smaller margin than Clinton won them by in 2016). In the end, their economic futures mattered more than Trump’s missteps over Covid-19, personality, lies, and social pathologies.

The conventional political wisdom has been that, as American society as a whole grew wealthier after the Second World War, politics shifted from being a battle over economics – between capitalists and the industrial working class. Instead, it became one over cultural issues: race, religion, and sexuality. Most observers have expected this cultural, rather than economic, divide to continue and grow. That assumption has become even stronger in the last four years, as scholars have concluded that Trump voters are motivated primarily by white supremacy, not economic anxiety. The behavior of the suburbs in this election disputes that easy assumption.

Education has also become a major factor. A leading Republican pollster who told me over a year ago that Trump was going to lose Georgia emailed me just after this election, saying:

“It appears that education level is becoming the defining factor of partisanship with a swap from how things were decades ago. Now working-class folks identify with the Republican party, and higher-education/higher-income folks see themselves as Democrats.”

As for the swing states that Biden appears to be flipping in this election, he commented, “With a good candidate, the GOP can win statewide. The problem is that the ‘burbs hate Trump.” In fact, in this uniquely racially polarized year, exit polls show that the only demographic group with which Trump lost ground from last time was white men. More than race, the emerging transformation of American politics lies along economic fault lines, not cultural ones.

Diversity Disjunction

If the suburbs represent the “diagonal” of progressive cultural values but conservative economics, then the inverse might be defined by America’s racial minorities: The other significant shift that this Election Night revealed, which came as something of a surprise to most, is that Latinos and African-Americans – mostly men – drifted toward Trump.

As this CNN analysis illustrates, Biden performed marginally less-well against Trump than Hillary Clinton did amongst almost all demographic subgroups. Even where he did better, Trump’s share of the vote generally held firm – Biden’s margin was higher simply because the third-party anti-Trump vote was lower. Despite mishandling a pandemic, presiding over a recession, getting impeached, and provoking civil strife unparalleled in 50 years, Trump’s support remained steady or improved over the last four years with virtually every demographic. But the most noticeable improvement came with Americans of color.

This fact defies common understanding. Trump has been viscerally anti-Hispanic: from his campaign announcement in 2015 that essentially branded all Mexicans rapists and thugs, to his policies of blocking almost all crossing of the southern border and separating immigrant children from their families, locking them in cages, and then losing track of the parents. But Hispanic Americans are not a monolith. Trump has aggressively courted Cuban-Americans and Venezuelan-Americans with his foreign-policy assaults on the Cuban and Venezuelan regimes and his verbal assaults on “socialism,” even while belittling Mexican-Americans and Puerto Ricans.

That explains Biden’s disappointing margin in Miami-Dade County, which doomed his attempt to flip the Sunshine State. But the Democrats’ long march to dominance in such southwestern states as Texas and Nevada also hit a roadblock in weakening Hispanic support overall. Biden won Nevada, but Trump’s vote doubled this year in counties lining the US side of the Rio Grande.

There has been speculation that growing Black and Hispanic affinity for Trump is tied to an appreciation of his over-the-top attempts at machismo. (How many ways can you use the word “powerful” in a sentence?) I think this wishfully underestimates how minorities in this country would sympathize with the GOP.

These minority voters are more religious, culturally conservative, and entrepreneurially aspirational – all ostensibly “Republican” traits – than generally perceived. Hispanics, like most immigrant populations, are highly entrepreneurial and came to American because they view it as a land of opportunity. In Nevada – where Biden slipped from Clinton’s 2016 margin – the Hispanic population, like the population generally, is highly dependent upon the visitor industry and thus profoundly affected by economic “lockdowns.”

African Americans, Hispanics, and, of course, religious minorities also tend to be more religious than the average American voter these days. As such, while Americans of color may not condone the racist, xenophobic drift of the Republican party, they are in sympathy with its broader policies.

There is also reason to suspect that – like working-class white Americans – there’s a lot they don’t like about Democrats. In my post-election conversation with the Republican pollster, I responded to his comment as to the new socio-economic divide between the parties:

“I believe Democrats should be the voice of those who are doing less well and are left behind by the economy, but the party is becoming one for the well-off. The liberal revulsion at ‘deplorables’ because of their religious and cultural beliefs greatly disturbs me; I find it both morally and tactically wrong.”

His response: “The strategy does seem to be turning some voters off, hence the loss of the Latino & African American vote share.”

Many Democrats have recognized this “elitism” problem, but it’s generally conceived as alienating the white working class. In fact, it’s also affecting minorities – the national exit poll shows the Democratic margin among African Americans fell by five percentage points this election. It has decreased every cycle since Barack Obama’s first election. Now it is at the lowest level this century – mostly going unremarked.

Don’t overreact. Democrats still hold a significant edge amongst Latinos, African Americans, and all Americans of color. It’s just not as massive of an advantage as before. But in a closely-divided electorate, even a slight shift can have considerable repercussions – like Florida, Georgia, Texas, Arizona, and Nevada have just demonstrated.

What The Future Holds

Since Barry Goldwater, Republicans have been refashioning themselves as the party of the declining industrial working-class, Christian fundamentalism, and white supremacy. In response, since Bill Clinton’s presidency, Democrats have been remade as the party of the future economy. Under Obama and then Trump, this transition has become complete.

Of course, it’s better politically to be the party of a growing and ascendant majority than a declining economic and demographic minority. The white vote is declining as a share of the electorate by roughly a half-dozen percentage points per presidential cycle, and the industrial workforce is declining inexorably, as did the agricultural workforce before it. Meanwhile, today’s share of Americans with college degrees is triple what it was when Richard Nixon was re-elected. The percentage with advanced degrees today equals that of college graduates 50 years ago.

Democratic constituencies, in short, are growing inexorably, while Republicans rely on a dwindling demographic. Suburbanites are increasingly sympathetic to progressive social goals. They are unlikely – even in the South, the Sunbelt, or in the increasingly conservative areas of the Rust Belt – to support candidates who blatantly violate the country’s new social norms. That doesn’t bode well for the many Republicans who tied their political fortunes to Trump. Most of them, especially those who hope to run for president in 2024, continue to do so during the current vote-count controversy.

On the other hand, other than Trump, very few Republicans – most notably Senators Cory Gardner (R-CO) and Martha McSally (R-AZ), who lost their re-election bids – were punished in this election either for Trump’s behavior or their own. Instead, suburbanites’ receptivity to traditional Republican economic policies make it likely that suburbia is a weak long-term bet for Democrats absent Trump.

There are also similar warning signs for Democrats on their other flank. A growing, not-insignificant number of Americans of color find liberals’ increasing economic elitism and interventionist policies less appealing than a traditional GOP prescription of equal access to a laissez-faire American Dream. As American culture becomes less fixated on race as a relevant differentiator, it should not be surprising if today’s racial minorities become more like the rest of the country, particularly suburbia, in the diversity of their politics.

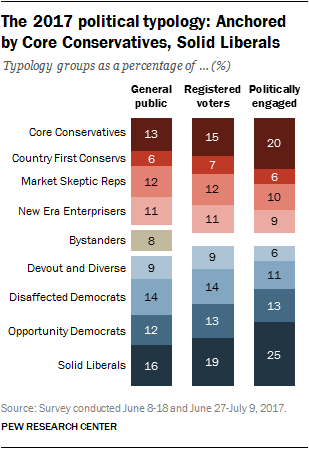

This may surprise many in the Democratic Party, but similar evidence has been visible for some time. The next generation of Americans who will shape the electoral landscape is generally presumed to be substantially more progressive than their elders. The sophisticated voter taxonomies of the Pew Institute have shown for several years that younger Americans largely fit the emerging pattern I just outlined for minorities and suburbanites: a belief in progressive values, including social justice and environmental consciousness, but a weak faith in government solutions. While voters under 30 rallied to Biden’s cause, providing him a 5-point larger margin than Clinton, his margin amongst 30-44-year-olds shrank by 40%.

The emerging pivot point in American politics, then, may not be quite what either progressives or Trumpists might want it to be. It will be the moderate voters who reject the attitudes and anger of what has become the Republican base but dismiss what they see as Democrats’ big-government answers. I suggested a possible resolution to this dilemma here in The Atlantic six years ago.

Neither party is formulating such a plan by any means, but they will have to as the country continues to change. Historians argue on what to call each political chapter in American history, but for the sake of simplicity, we are currently entering the sixth great party system in American history. It was begun by Bill Clinton, solidified by Obama, and taken to its extreme by Trump. As with everything, Trump’s extreme nature is probably bringing the current system to an abrupt bankruptcy within a single generation. The next party system is beginning to take shape, and it is doing so in places that people wouldn’t think to look: amongst socially liberal suburbanites and socially conservative minorities.

The good news is that this realignment appears to be centered on economic issues, which are more susceptible to compromise than cultural concerns. The bad news is that no-one yet has figured out how to bring together cultural conservatives and cultural liberals to fight for the rights of those dispossessed by the New Economy. Unfortunately, that will be most of us.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________