Easter Sunday, 1995, was a beautiful day. An assortment of daffodils in joyful bloom greeted me at the end of my parents’ driveway as I returned home from college for the weekend, a much-needed break before final exams. My parents hosted both sides of the family that day, so we had a houseful of cousins, aunts, uncles, and grandparents. The adults were busy preparing the meal and setting up various outdoor games. From my sister’s bedroom in the back of the house, a cavalcade of the youngest cousins sprinted noisily through the kitchen to get to the activities outdoors. As they ran past, great-grandma Pauline was mid-slug of beer, so the pounding of their bare feet had already dissipated by the time she hollered at them to be careful. Once the food was eaten and the dishes were cleared, I flitted from one activity to another, playing some volleyball on the makeshift court in our front yard, joining in the basketball game on our driveway, and, the rowdiest activity by far, playing a few rounds of cards at the dining room table.

It was the last day we would all break bread or play together as a fully intact family. Three days later, my dad would be dead. On April 19, 1995, Timothy McVeigh pulled up to my dad’s office building. He had a truck filled with explosives and a soul filled with hate. He murdered my dad and 167 other innocent people.

Thirty years later, I worry that many in our country have forgotten, or don’t know, what led up to McVeigh’s actions in 1995. My engagement with social media began as a fun way to stay in touch with those far away, receive updates on friends’ families, and see (often with envy!) people’s fabulous vacation photos. Recently, however, much of what I see resembles the sentiment that McVeigh devoured. People are cheering those who set fire to Tesla cars; some are lauding Brian Thompson’s murder; some are excusing those who stormed the U.S. Capitol with violent intentions. Mark Twain said, “History doesn’t repeat, but it rhymes.” If he’s correct, we are engaging in the poetry of misery. McVeigh became radicalized the old-fashioned way, by marinating in hateful books and angry radio shows. I see echoes of his perspective everywhere now that it’s become much easier to hate and vilify “the other side,” even tragically, within our own families. Looking back on my family’s Easter gathering in 1995, we were an incongruous mixture of humanity: blue-collar, white-collar, bearers of high school diplomas and college degrees, liberal, conservative, country mouse, town mouse. I fully loved – and always will love each of them.

When the bombing happened, our country stood unified. People waited in hours-long lines to donate blood, millions of dollars flooded into Oklahoma City to help those impacted by the Bombing, first responders were given meals and housing, people everywhere wore ribbons of support, and everyone denounced McVeigh’s actions. Doctors didn’t check Voter ID cards before they treated a patient. Donors didn’t demand that their blood and money only nourish those with whom they agreed politically. President Clinton, a Democrat, and Governor Frank Keating, a Republican, were unified in comforting our city and lockstep in finding and punishing the perpetrator. Their reciprocal respect was evident, and their mutually demonstrated leadership helped pull our city back from the brink of despair.

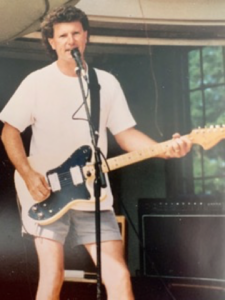

After the Bombing, I shied away from conversations about my dad’s death. I didn’t want to be attached to our nation’s worst act of domestic terrorism. I only wanted to grieve my dad singularly, but that’s never been possible. After three decades, it still breaks my heart each time I revisit 1995, but I feel a renewed sense of urgency to share what my dad’s death meant to me and how it continues to affect me. My dad was young. He was fully alive. He had plans for his future. He had a big, infectious laugh. He loved music and played guitar. When he sang, he sounded like Tom Petty, but when I think that we as a country have forgotten what led to the Bombing on April 19, 1995, I’m the one who feels like she’s free falling. We can’t forget the hateful anger that motivated a young man to murder 168 of his fellow Americans. Together, we must renounce hate and violence everywhere we see it, and we can’t give up on demanding courageous leaders who prioritize respect over politics.

Sara Sweet lives in Oklahoma City. Her father, W. Stephen Williams, was killed in the Oklahoma City Bombing.