Photo by Dan Meyers | Unsplash

A mail carrier in rural Florida dies after being attacked by five dogs. A nine-year-old is attacked by a mountain lion in Washington State. A black bear attacks a woman in Vermont. These stories are so common that few of us pay them close attention anymore. And fewer still would think that the U.S. Constitution provides us with a helpful solution to these attacks. But it does.

When it was ratified in 1791, the Second Amendment’s core purpose was to provide the individual with the private right to self-defense. That right was an all-encompassing term, the ambit of which we generally see as extending to defense against criminals, agents of a tyrannical government, foreign invaders, and the like. But defense against animals was also a crucial part of the self-defense equation at the Founding, and so it remains today.

The American frontier of the 18th and 19th centuries was filled with vast unknowns, and its inhabitants were on their own when attacked. From venomous rattlesnakes to vicious grizzlies, to wild boars, one never knew—and seldom saw coming—the dangerous creatures of the American continent. Indeed, it is in this context that now-retired Justice Anthony Kennedy rhetorically asked Petitioners’ counsel in District of Columbia v. Heller whether the right to keep and bear arms “had nothing to do with the concern of the remote settler to defend himself and his family against hostile Indian tribes and outlaws, wolves and bears and grizzlies and things like that?”

Today, much of rural America remains as remote and self-sufficient as the frontiers of old. And rural, urban, or otherwise, the swift onset of an unprovoked animal attack affords no opportunity for anything but the ablest of self-defense. Bystanders, if there are any, are often helpless in the face of animal attacks, and their courage to intervene cannot always be counted on. As in the context of self-defense against criminals, we are our own first responders.

Nor can we count ourselves safe simply because we do not live in a rural area. Brazen wild animals often wander into suburbs and cities, and even domestic dog attacks account for 50 human deaths a year.

In June, the Supreme Court decided a seminal case, New York Rifle and Pistol Association v. Bruen. In it, the Court reinforced a framework of Second Amendment interpretation that required courts to closely analyze American history and tradition in determining the scope of the right to keep and bear arms. And that history and tradition illustrate the longstanding necessity of Americans to protect themselves from animal attacks. In fact, the wild animal populations had grown so out of control and instilled so much fear in the settlers that colonies like Massachusetts and South Carolina began to place bounties on the heads of animals like wolves, bears, bobcats, and panthers.

For an illustration of the dangers of the American frontier, one needs to look no further than the following event involving legendary frontiersman Daniel Boone. Boone and his brother, Neddie, were hunting when they stopped by a stream to rest. Daniel spotted a bear rustling in the woods; he proceeded to shoot and follow it while his brother Neddie remained behind. Then, hearing gunshots, he saw a handful of Shawnee Indians over his brother’s corpse, which they had decapitated. With the Indians on his tail, Daniel ran to Boone’s Station. When he returned with a posse to the site of Neddie’s killing, he found his brother’s corpse eaten by a panther. In one founding era gun story, we have a beheaded corpse, a panther, a bear, and Indians.

America’s wilderness and rural settings can be dangerous today, and one always must be prepared for surprise attacks from unseen quarters. This is especially true of those who visit or travel through these parts since they are the least likely to know how to avoid attracting the attention or interest of wild animals.

The history and tradition of our Nation and our Second Amendment clarify the importance of self-defense in the face of animal attacks. The pre-existing right of self-defense is, as the term suggests, focused on the self. The aggressor’s identity does not matter; man, woman, or animal, a person has an equal right to defend himself or herself from anyone and anything by whom or which his life is threatened. Given that backdrop for the Second Amendment and early American history, it is quite difficult to see how protection from animals could not be one of the key applications of the right to keep and bear arms.

Justice Alito’s concurrence in Bruen concluded with the following observation, which is as applicable to self-defense from animals as it is to self-defense from other humans:

Today, unfortunately, many Americans have good reason to fear that they will be victimized if they are unable to protect themselves. And today, no less than in 1791, the Second Amendment guarantees their right to do so.

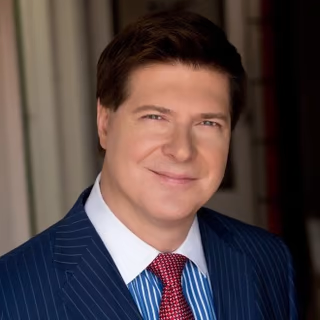

Mark W. Smith

Mark W. Smith is Visiting Fellow in Pharmaceutical Public Policy and Law in the Department of Pharmacology at the University of Oxford; Presidential Scholar and a Senior Fellow in Law and Public Policy at The King’s College; and Distinguished Scholar and Senior Fellow of Law and Public Policy at the Ave Maria School of Law.

He is a constitutional attorney and Host of the Four Boxes Diner YouTube channel—which provides scholarly and historical analyses of the Second Amendment. Mark is also a New York Times bestselling author.