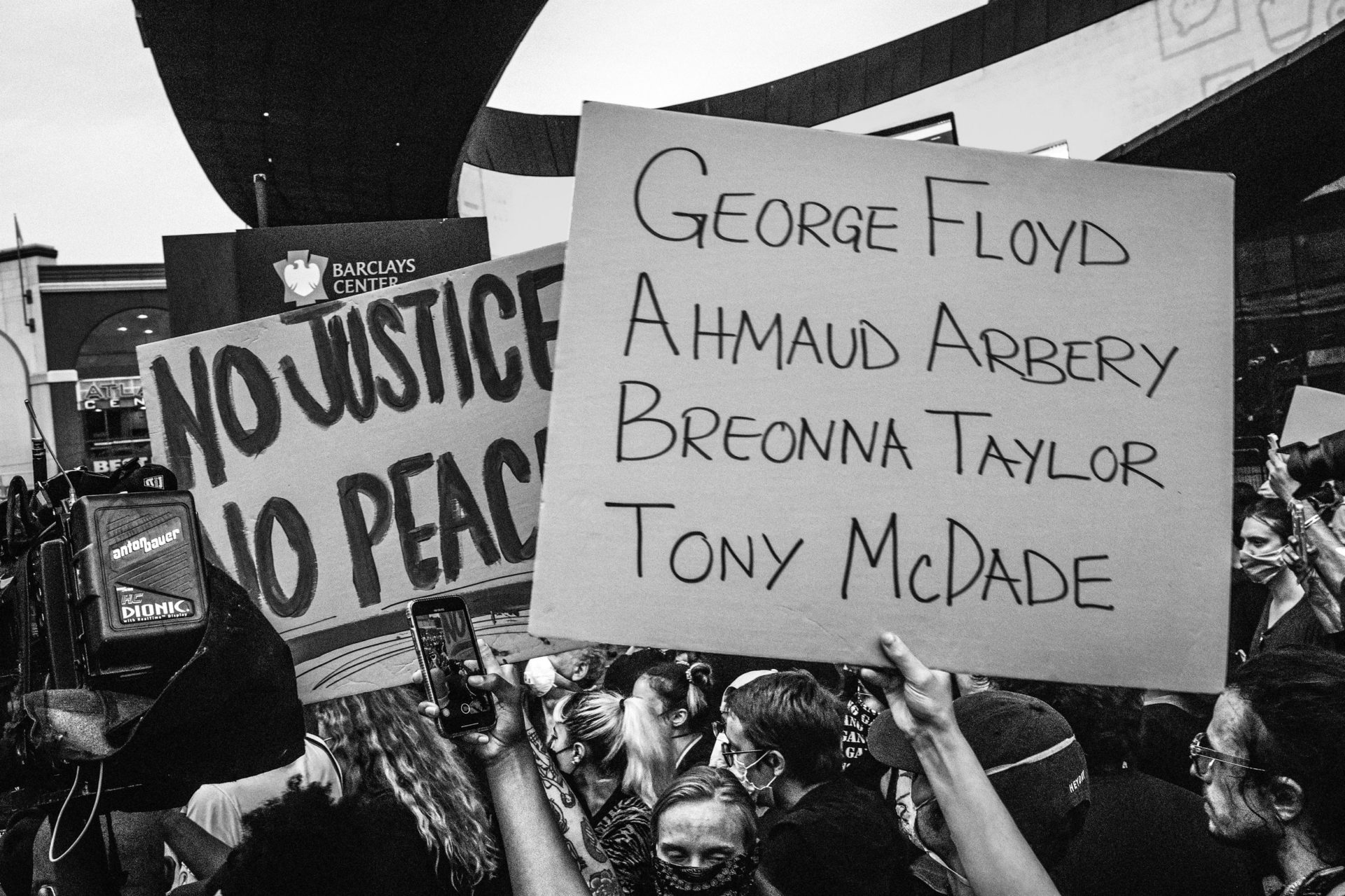

Did prosecutors in the Georgia trial of Ahmaud Arbery’s killers make a big mistake? These legal eagles spent more than a week trying to convince an almost all-White jury that the three men implicated in the February 2020 death of the Black jogger were guilty of murder, but they apparently failed to use the most potent weapon available: the defendant’s own words.

I’ve observed a lot of headshaking and handwringing by non-lawyer armchair quarterbacks who wonder how the state’s attorneys could have made such a mistake. The prosecutors cross-examined Travis McMichael, the defendant who pulled the trigger on the murder weapon, but they never asked him about the racist words he uttered. Those words are troubling, to say the least.

According to law enforcement officials, McMichael’s co-defendant William “Roddie” Bryan Jr. asserted that McMichael used racial slurs, including the n-word, right after the shooting, as he stood over Arbery’s bloody body. We must assume that any jury in their right mind would convict someone who did this, but prosecutors never once talked about racism or bigotry. What were they thinking?

As a former prosecutor myself, I’d say they were thinking smartly. The state didn’t need to prove a racist motive. There was plenty of evidence of racism – such as a Confederate flag symbol on the defendant’s truck – but the state’s case was based solely on the defendants’ actions, not their motives. The jurors only needed to hear how the three men chased Arbery through their neighborhood and shot him. The only question for them to decide was whether those actions were legally justified.

Prosecutors could have seriously jeopardized their case had they introduced Bryan’s statement. It was non-hearsay under the rules of evidence because it was an admission, but once Bryan invoked his Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination, he effectively shielded himself from cross-examination by McMichael’s attorney.

Under the Sixth Amendment to the Constitution, every criminal defendant a right to confront witnesses against him, which is known as the “Confrontation Clause”. And the clause applies to Travis McMichael as well. The Supreme Court has even ruled that prior testimonial statements of witnesses who are unavailable for any reason may not be admitted without cross-examination. To introduce Bryan’s statement without allowing such confrontation would have undoubtedly been grounds for a mistrial.

What about other signs of bad intent, such as racist text messages and emails McMichael sent to friends and family? An appellate court would likely find these too prejudicial to the defendants. Under Rule 403 of the Federal Rules of Evidence, a court can exclude relevant evidence if its probative value is outweighed by a danger of unfair prejudice, and under the exact same rule in Georgia, Rule 24-4-403, a state court could easily find the texts and other communications too far removed from what happened to Arbery.

The bottom line is the state’s case is a strong one. Even without evidence of overt racism, the facts are compelling. Three white men chased down a lone Black jogger who was clearly unarmed, they corralled him with their trucks, and they shot him at point-blank range. Why would prosecutors risk a mistrial with such a strong set of facts?

But there is also a federal case that will be made against these same defendants. That case will charge these same defendants with hate crimes, requiring a completely different set of findings. Hate crimes require proof of motive, and juries will have to consider what defendants were thinking and feeling and intending when they committed the crime.

Although double jeopardy (i.e., the legal principle that a defendant cannot be charged for the same crime twice) doesn’t apply when there are separate state and federal cases because of the Dual Sovereignty Doctrine, typically the federal government won’t pursue a case once a state court has heard it. The Petite Policy says that the Department of Justice will not authorize the expenditure of federal funds to pursue a case that has already been resolved. The exception, however, is when a case implicates a “compelling federal interest” not vindicated in the state court.

The Arbery case is a perfect example of this exception as Georgia was one of the few states without a hate crime statute. For a federal hate crime, what McMichael said – while standing over Arbery’s body and even perhaps when texting his buddies – is absolutely relevant. It could, in fact, be the most critical piece of evidence the government can introduce.

Federal prosecutors thus have two possible paths. They could choose simply to present the facts and let those facts speak for themselves: vanity license plates, a Confederate flag, a black man dead. Or they could decide to pull an ace out of their sleeve and grant immunity to Roddie Bryan, compelling him to testify.

If they do the latter, Bryan has no Fifth Amendment right to remain silent, and when he takes the stand, Travis McMichael can no longer hide behind the Confrontation Clause. Bryan will walk free on hate crime charges, but McMichael will almost certainly be convicted. Assuming the defendants are found guilty in the state trial, we may see federal immunity for Bryan. He will already be serving time for a crime. However, should Bryan be acquitted on the state charges, it is unlikely that federal immunity will be granted. Prosecutors will want all defendants to be held accountable for their actions.

As we await verdicts in the Georgia case, federal prosecutors will also be watching and making their plans.

Neama Rahmani

Former U.S. Assistant Attorney Neama Rahmani is the co-founder of West Coast Trial Lawyers in Los Angeles, which represents plaintiffs in personal injury and employment litigation.